By: Margrét Pála Ólafsdóttir.

To many adults, the world has shrunk. It only takes us a short while to travel between places, countries and continents – over hundreds and thousands of kilometres or miles – distances that in the eyes of our ancestors corresponded to light years. The seventeenth of next month, the third week next year, pop over to a conference, a golfing trip with the club, a meeting overseas and then home again.

Children do not understand such use of language or this type of reality. They have the ability of living in the present, and their thinking is object orientated, i.e. they want to see, touch, hear and feel here and now what is going on. This is why parents must prepare their children before one or both of these most beloved persons in the world “pops off” to another part of the world and then keeps in contact with the child at home.

A child’s knowledge of the imminent absence of a parent can cause the child agitation or anxiety, particularly if the child has previously experienced separation anxiety. As a result, it is best not to tell the child about the absence too early but just early enough so that the child can adapt to the thought. Less than a week is usually enough for most children, and in order to minimise the child’s agitation, it is best to explain matters in some detail. Show your child pictures of the place you will be visiting. In addition, it might be a good idea to print out a map of the world, and you and your child can draw in the route you will be taking. Explain the reason for the travel to your child so that he or she understands what you will be doing while you are away. The child can then imagine the mother, for instance, at a meeting telling people about all the fun things she is doing at work. You could also show the child the prepared presentation that the mother intends to use. This conversation and viewing of pictures and other understandable documents will also allow the child to imagine the father in the room in the hotel or on the train at the destination according to the pictures you viewed together in the computer. The more the child knows about the trip, the better he or she will feel during the absence. Do not underestimate children; they will understand you if you use the type of language that is suitable for their age and development. Remember to use as much visible material as possible.

It is also a simple matter to help children understand how long the trip will last. A good idea is to prepare a simple calendar where the child can cross out each day in the evening or in some positive manner “see” how each day passes. The absent parent should also contact the home, send pictures and let the child know what has been happening – preferably always at the same time of day suitable to the general rhythm of home life. Use good sense, and do not, for example, phone home just before bed-time, as this can disturb the child and serve as a reminder of the separation.

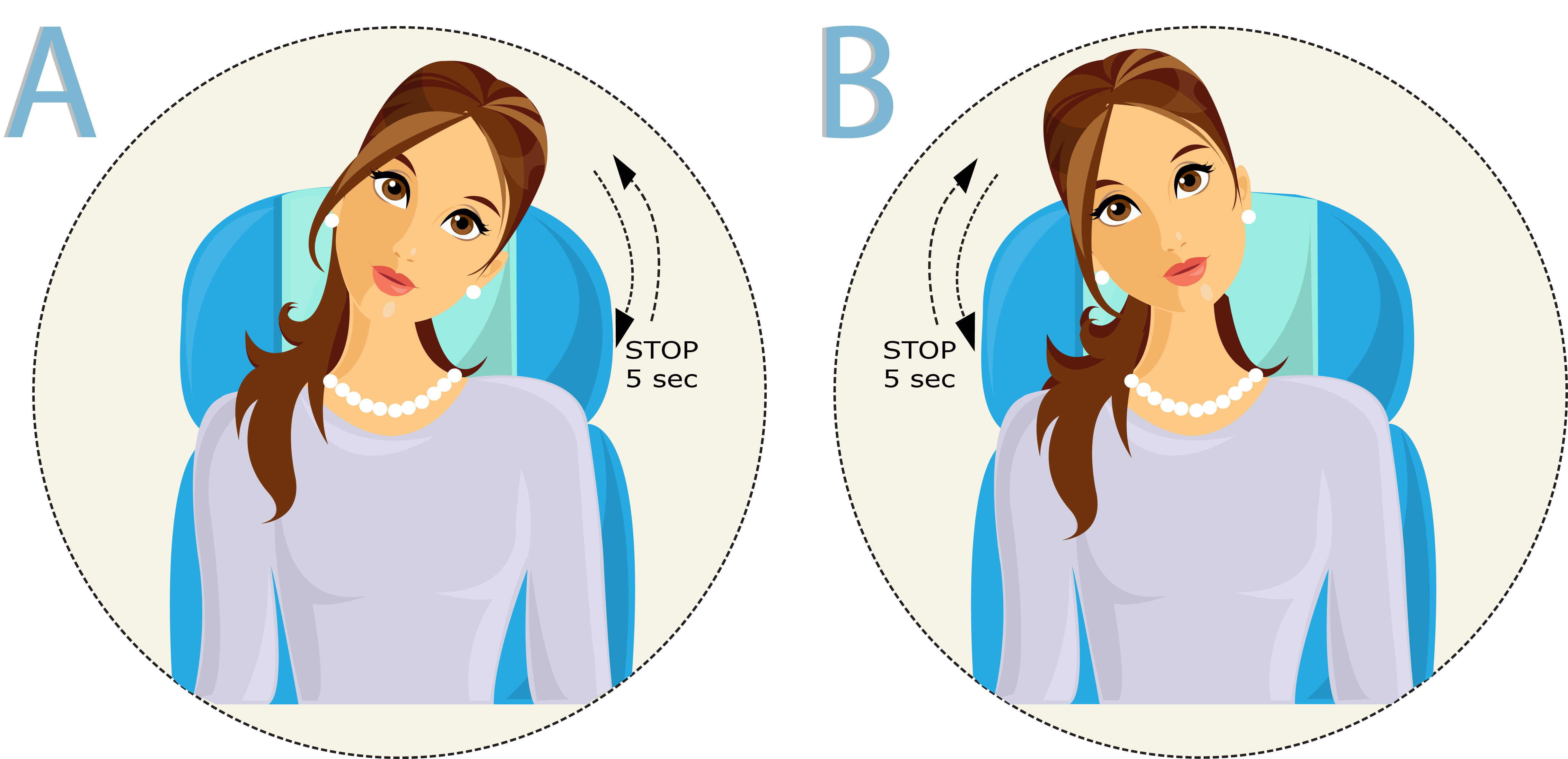

Remember that protracted and difficult good-byes do not lengthen positive togetherness but rather draw out the separation. Short and lively goodbyes are best, as this will help the child know that you are alright. The same applies when you come home. Do not make too much of a fuss about the homecoming as this tends to make the child feel as if the absence was a bigger deal than it experienced. A small gift together with hugs and kisses is, of course, quite acceptable as a positive and concrete confirmation about the places that the child knew that mum or dad would visit. Moderation in all things is best.

Have a nice trip.

Margrét Pála Ólafsdóttir is the author of Hjallastefna (Hjalla policy). Hjallastefna is both a methodology used in nursery and primary schools as well as an educational company that operates numerous nursery and primary schools in Iceland. Margrét Pála is educated as a nursery school teacher, has a diploma in school management, M.Ed in child development and teaching and an MBA diploma.